Béla Bartók’s Significance in Hungarian Folk Music Research

Bartók’s significance in Hungarian folk music research is not only due to the fact that he began systematic fieldwork at an early date, or that he discovered the role of pentatony in old Hungarian melodies – although this discovery alone would be sufficient for us to remember him as a leading representative of Hungarian ethnomusicology. Pentatony was to exert a decisive influence upon the compositional workshop of Bartók and Kodály, and to play a decisive role in the debate, carried on since the 19th century by both professional musicians and the public discourse, on what to consider authentic Hungarian music. By then, the 19th-century verbunkos style had already been worn out, and offered no more than musical common places. Instead, Bartók and Kodály found in the descending, fifth-shifting pentatonic songs a melodic structure and a tone system free from the influence of Western art music, something they could rightfully consider genuinely Hungarian. This revolutionary discovery led to Kodály’s national programme of the 1920s, advocating for folk songs as one of the most important components of music education.

Yet the significance of Bartók as a folk music researcher cannot be reduced to a single discovery, but it implies the whole of his scientific output: the processing and study of his collections of about 10,000 tunes, the conclusions he had drawn, and his specific methodologies. In this respect, we should mention four areas: (1) the methodology of folk song transcription; (2) comparative folk music research, resulting from the analysis of the music of neighbouring ethnic groups; (3) the classification of the Hungarian, Romanian, and Slovak folk music repertoires according to musical criteria; and (4) collections of instrumental music and descriptions of folk instruments.

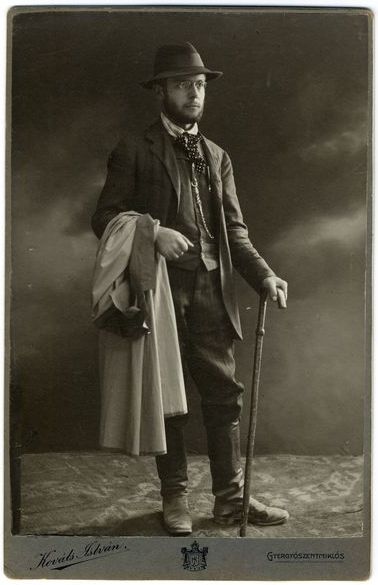

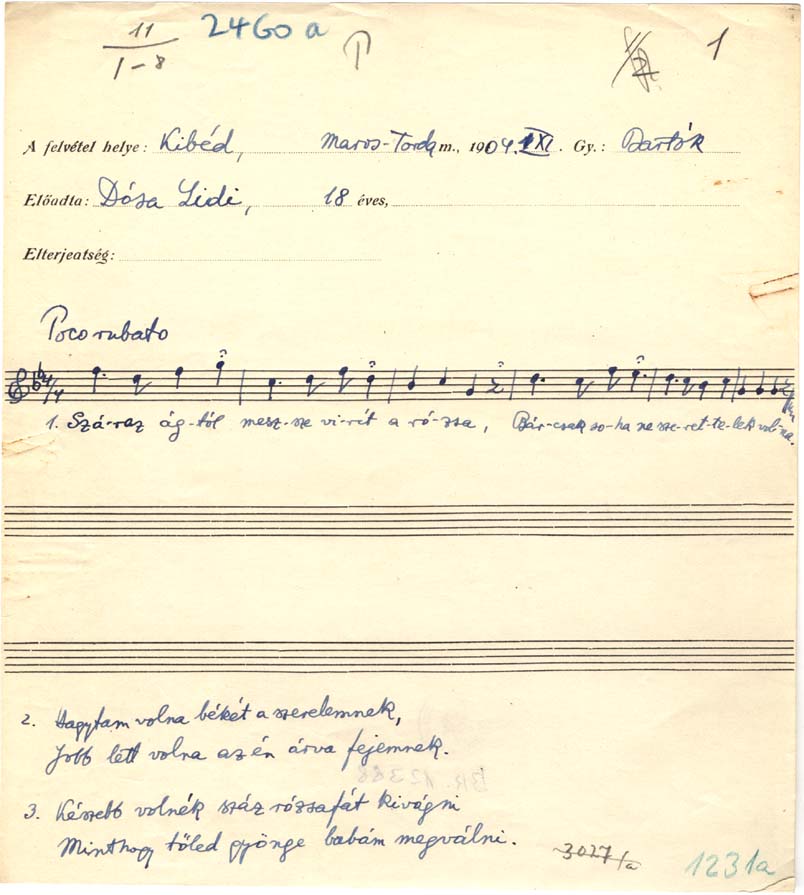

Bartók’s first year of substantial folk song collection was 1906. Previously, in 1904–1905, he had transcribed a few melodies, some during a visit at his brother-in-law’s in Vésztő, Békés County. From May until the end of July and then from late August to early November 1904, he was a guest of the Fischer family in Gerlice-puszta, Gömör-Kishont County (today: Grlica, Gemerská, Slovakia). It was here that he met the maidservant Lidi Dósa, who came from the Transylvanian village of Kibéd (today: Chibed, Romania), and immediately impressed Bartók with her songs. He transcribed five melodies, dated in July, and three more in November. From then on, as Kodály recollects, Bartók was infatuated with Transylvania and Székely folk music in particular.

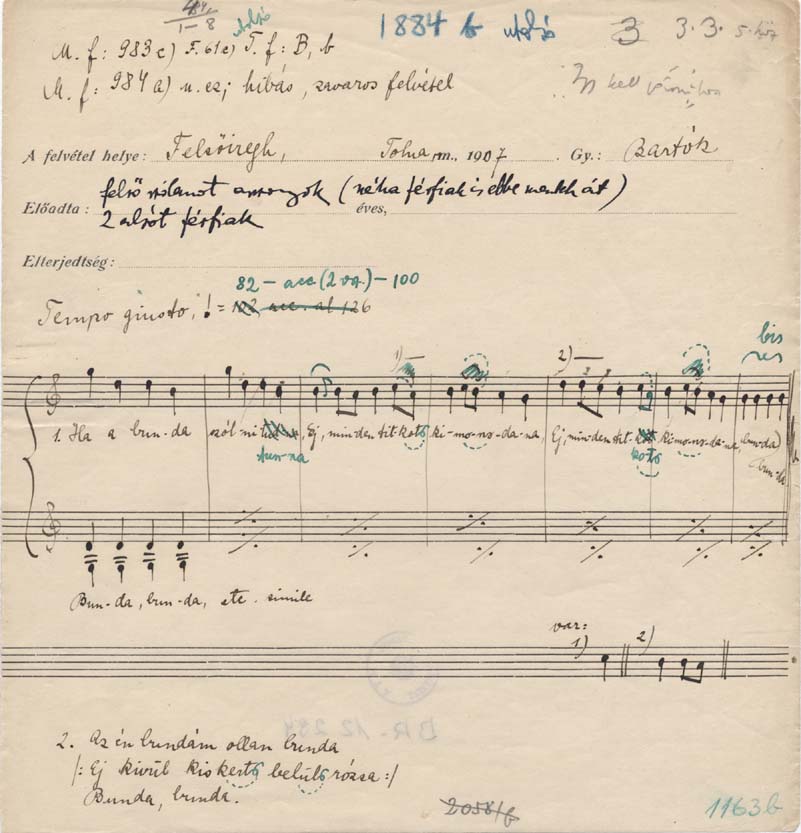

Among the eight melodies collected from Lidi Dósa, the only pentatonic one is a fragment (Figure 2). However, the year 1906 saw a real breakthrough in folk music collection. During the summer and the autumn, as well as in December, Bartók collected more than 1,000 Hungarian songs from the Southern Great Plain, Transdanubia, and Pest County, and about 300 Slovak songs in Gömör-Kishont County. In 1907, he continued at an even faster pace. He collected about 700 Hungarian melodies during the spring in the Transdanubian village Felsőireg (today: Iregszemcse, Tolna County) and, during the summer, in the Transylvanian regions of Csík and Gyergyó, while he carried on the exploration of the Slovak material. He began his Romanian collections two years later, in July 1909, in Belényes, Bihar County (today: Beiuș, Romania), and its surroundings.

Due to his concert tours, Bartók continued the collection with varying intensity; still, he collected large quantities of Hungarian, Slovak, and Romanian material every year until 1914. He was interested from the outset in comparing the folklore of different peoples, and in tracking the melodic and stylistic borrowings. This is the reason why his collections contain roughly the same proportion of Hungarian, Slovak, and Romanian folk music. But his interest led him on to distant peoples: he conducted fieldwork in Algeria in 1913, and in Turkey in 1936. Thanks to the Algerian collection, he was invited to participate at the first international conference on Arabic music, held in Cairo in 1932. Following Béla Vikár, Bartók used the phonograph from the very beginnings to complete his field notes with sound recordings. His field trips came to an end with the partition of historical Hungary after World War I.

Folk Music Transcription

For Bartók, transcribing the melodies was an important component of the scientific preoccupation with folk music. From the very beginning, i.e. 1905–1906, Kodály and Bartók took advantage of the period’s technical innovations, recording a part of their collections on phonograph cylinders. Béla Vikár was one of the first to use the phonograph for folk music collection at the end of the 19th century. Most of Vikár’s recordings were transcribed by Bartók during the 1910s. While Kodály and Bartók had different opinions about the significance of phonograph records in folk music research, they agreed that the phonograph was an indispensable tool for a scientifically valid collection. Kodály’s approach focused on the folksong’s typical, essential form. Bartók, on the other hand, tried to render the audible form as accurately as possible. During his long activity, Bartók became “an epoch-making, in a certain sense unique master”2 of folk music notation. As Kodály stated in his recollections of “Bartók the Folklorist” in 1950,

His written records represent the ultimate limit to be reached by the human ear without the aid of technical instruments. After this, only sound photography can follow.3

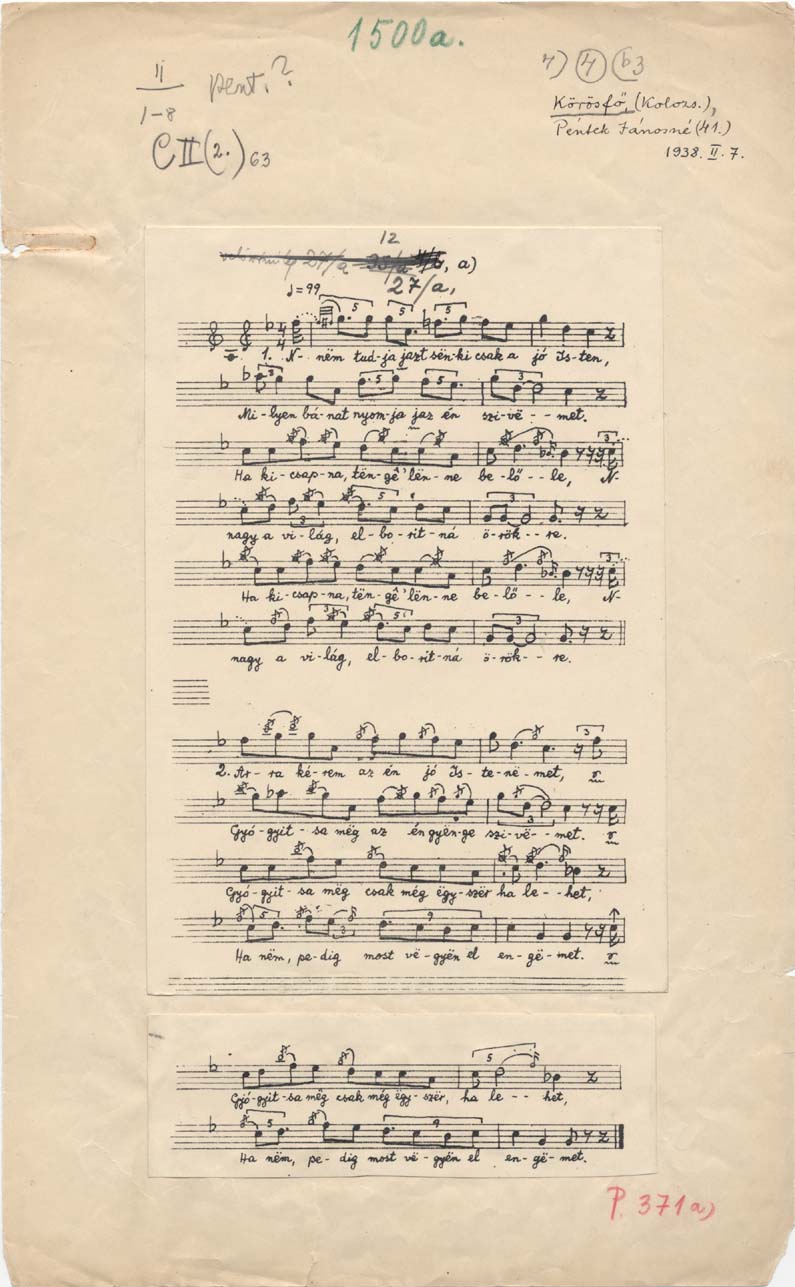

By exploring the developmental stages and temporal layers of these transcriptions, we can systematically trace back the phases of Bartók’s scientific approach, with its ever increasing precision and concern for the smallest details. Bartók developed his meticulously detailed and accurate transcription technique, and the special notation connected to it, in several decades. Regarding the method of collection, the manuscript folk music transcriptions, which also record the ethnographic data of the collection, the text, etc., can be divided into two large groups: field notations made on the spot and subsequent transcriptions of audio recordings. The availability of an audio recording, and the possibility of repeated listening, is crucial for a detailed transcription.

Bartók considered folk music – or “peasant music” as he preferred to designate it – a natural phenomenon, comparable to figures of flora and fauna. (He was also a passionate insect and plant collector, leaving behind a significant collection of butterflies.) For him, therefore, the re-playable audio recording was an important device of folk music research in the spirit of the “natural sciences,” as it made possible the examination of any tune (even though phonograph cylinders only permitted a limited number of re-plays). By slowing the playback speed, he could observe the smallest details, similarly to a microscopical examination. Bartók tried to transcribe the folk songs with an accuracy characteristic of the natural sciences:

The rotational speed of the record can be decreased… by such means we can notate the very intricate or hardly perceptible ornaments and rhythmic differences with an accuracy unobtainable from hearing the natural song, no matter how often it is performed. Finally, the phonograph provides one of the very best means for achieving the ideal aim in our collecting and investigative work on folk songs: elimination of the subjective element… as long as human labour is involved in the process, there is no doubt that subjective elements will be included in the recording, the classification, and so forth.4

By transcribing, correcting, and re-transcribing hundreds of hours of recorded material, Bartók reached the final phase of his special notational technique, which we may call microscopically detailed transcription. The stages of this development can be reconstucted from manuscripts and printed sources. In the last phase of his transcriptions, Bartók notated the ornaments in such detail that the additional publication of the melodic skeleton seemed necessary. If possible, Bartók notated every rhythmic relation (including the rhythm of the tremolos, the glissandi, or other ornaments not audible under normal circumstances) and, as a result, he omitted the relative, non-exact rhythmic signs he had used referring to slightly longer or slightly shorter values. He determined the rhythmic value of the metronome mark according to performance style (MM quarter for tempo giusto, MM sixteenth for rubato, MM eighth for some unique melodies, such as those in 6/8 and 3/8). In rendering hiccup-like ornaments, he distinguished uncertain pitch from firm, regular pitch (Figure 3). In terms of transcription technique, Bartók’s Turkish collection (November 19–20, 1936) belongs to the late, mature type of his transcriptions. This collection was published posthumously, in 1976, under the title Turkish Folk Music from Asia Minor.5

Comparative Research and Classification

For Bartók, folk music primarily meant a musical experience; the longing after the unknown, the wanderlust – undoubtedly Romantic emotions – acted as a strong incentive throughout his fieldwork. As Kodály remarks,

It is true that his collections in Romanian and other foreign languages are numerically superior to his Hungarian collection… his interest was attracted by the novelty and unfamiliarity of the material. As in everything else, he was novarum rerum cupidus in this, too.6

According to Bartók’s concept of scientific elaboration, the thorough exploration of the folk music of individual areas is to be followed by the second part of the research:

a comparison must be made of the material of the different areas in order to determine what is common and what is different; that is, the descriptive musical folklore is followed by the comparative musical folklore.7

Once he was acquainted with the folk music of the Slovaks and that of the Romanians of Transylvania, Bartók found an unusual richness of melodic types in this Eastern European territory. He explained the phenomenon as follows:

What can be the reason for this wealth? … Comparison of the folk music of these peoples made it clear that there was a continuous give and take of melodies, a constant crossing and re-crossing which had persisted through centuries… A Hungarian melody is taken over, let us say, by the Slovakians and ‘slovakized’; this slovakized form may then be retaken by the Hungarians and so ‘re-magyarized’. But… this re-magyarized form will be different from the original Hungarian.8

It is due, on the one hand, to this concept of comparative research that Hungarian ethnomusicology could reveal the connections of the Hungarian musical tradition both horizontally, that is in geographic context, and vertically, that is from a historical point of view. On the other hand, the classification of a huge material according to the criteria of musical analysis also contributed to the result. The founding fathers of Hungarian folk music research happened to be at the same time also erudite musicians and outstanding composers (Béla Bartók, Zoltán Kodály, László Lajtha, Pál Járdányi, etc.). Thus, from the very beginning, a great emphasis was given to the musical analysis and the musically based classification of the collected material. From a musicological and ethnomusicological perspective, this analytical and comparative processing of the collected material resulted in a number of significant scientific achievements. It helped to define the connections of Hungarian folk music with the neighbouring and related peoples; it revealed the stylistic layers within Hungarian folk music; and it attempted to explain the prevalence and the origin of the different styles. The publication of the massive material was based from the very beginning on musical criteria.

In The Hungarian Folksong, released in 1924, but already written in 1921, Bartók distinguished several musical styles whithin the material collected by then, such as the old-style melodies (Class A); the recently developed or currently emerging new-style melodies (Class B); and the large group of songs containing a significant amount of assimilated foreign elements (Class C). Due to the heterogeneous nature of Class C, no uniform style could emerge from it. Bartók defined these musical styles based on their musical characteristics (final notes of the melodic lines, structure, rhythmic formulas, etc.) and attempted to distinguish, in all three stylistic blocs, groups of identical or nearly identical tunes, i.e. melodic types. Later, from 1934 onwards, Bartók worked at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences on the compilation of a Universal Collection of Hungarian Folk Songs. He organized about 13,000 data according to a slightly modified system as compared to the previous ones. The project included a re-examination of the phonograph recordings, and a revision of his earlier transcriptions. Known as the Bartók System, this synthesis is a major document of Bartók’s scholarly achievement. (The critical edition of Hungarian folk music is still being carried out according to musical criteria in the series Corpus Musicae Popularis Hungaricae.9) It was again Bartók who distinguished the dialectal areas of Hungarian folk music as Transdanubia, the Northern Territory (Highlands), the Great Plains, and Transylvania.

During the same period, Bartók also worked on his Romanian collection, which he brought with him to the United States in October 1940 in the form of a fair copy. Out of the three volumes, the first two were completed by the end of 1942, while the third one in March 1945. The publication of the volumes took place posthumously. Here again the material was ordered and prepared for publication based on musical and textual criteria. A similar case was his collection of Slovak folk music (completed earlier, during the 1920s) which eventually appeared in print only in the decades following World War II.

Bartók’s Editions of Folk Music

Hungarian Folk Music

1908, 1909 “Székely balladák,” “Dunántúli balladák” [Transylvanian ballads, Transdanubian ballads], Ethnographia.

1918 Die Melodien der madjarischen Soldatenlieder, Universal Edition, Wien

(1921) 1924 A magyar népdal

1925 in German: Das ungarische Volkslied, Berlin–Leipzig

1931 in English: Hungarian Folk Music, London

1934 Népzenénk és a szomszédnépek zenéje [Hungarian Folk Music and the Folk Music of Neighboring Peoples]

Romanian Folk Music

1908, 1909 “Székely balladák,” “Dunántúli balladák” [Transylvanian ballads, Transdanubian ballads], Ethnographia.

1914 “A hunyadi román nép zenedialektusa” [The Folk Music Dialect of the Hunedoara Romanians], Ethnographia

1923 Volksmusik der Rumänen von Maramures, München

1935 Melodien der rumänischen Colinde, Universal Edition, Wien

(1945) 1967 Rumanian Folk Music

Serbian and Croatian Folk Music

(1945) 1951 Yugoslav Folk Music

Slovak Folk Music

1957 Slovenské ľudové piesne/Slowakische Volkslieder Band I., 1970 Band II, 2007 Band III.

Turkish Folk Music

1976 Turkish Folk Music from Asia Minor (revised edition: 2002, Péter Bartók)

Arab Folk Music

1917 A biskra vidéki arabok népzenéje [Arab Folk Music from the Biskra District]

1920 “Die Volksmusik der Araber von Biskra und Umgebung,” Zeitschrift für Musikwissenschaft June 1920, 489–522.)

2006 Bartók and Arab Folk Music / Bartók és az arab népzene (CD-ROM)

Instrumental Folk Music, Instruments of Folk Music

Traditional Hungarian musical culture is essentially monophonic. At the beginning of the 20th century, when Bartók and Kodály started the systematic collection of folk music, they found almost exclusively monophony, which thus gave their primary inspiration. As a musical phenomenon, monophony appeared sharply different from the polyphonic and harmonically based Western musical language. The soundscape of the monophonic Hungarian folk music must have been in itself a far-reaching discovery, also confirmed by the richness and particularity of its scales and the rhythmic diversity of the melodies. Indeed, it would have been almost inappropriate to see any harmonic aspect in this newly discovered musical universe, let alone such that could be linked to Western music. Especially at the beginning, Bartók and Kodály viewed the instrumental practice in folk music as an adjacent, marginal product of the vocal tradition. As Bartók wrote in 1911 in “The Folklore of Instruments and their Music in Eastern Europe,”

Our interest, of course, is only in music performed on folk instruments, as originating from peasant hands. A general rule: folk instruments – as we designate them – are only those instruments produced in the villages by the peasants themselves, without imitating some artificial manufactured instrument.10

Bartók’s definition ignored even those factory-made instruments which were widespread among the people, such as the clarinet or the violin. Instead, he focussed on the flute, the bagpipe, the zither, the hurdy-gurdy, and the swineherd’s horn. Kodály, in his study Hungarian Folk Music of 1937, was more permissive with regard to the use of instruments, but pointed out the difference in significance between the vocal and instrumental folklore:

The Hungarians are not especially fond of musical instruments. Relatively few individuals are able to play an instrument; even the poorer people hire professional musicians, rather than playing with their own hands. Therefore, there is little instrumental music compared to the richness of vocal folk music. [...] Among the musical instruments used by the people, some are made by themselves (Jew’s harp, swineherd’s horn, […] flute, bagpipe, zither; less often: cimbalom, hurdy-gurdy), others are factory-made (violin, clarinet, cimbalom, flugelhorn, accordion, harmonica).11

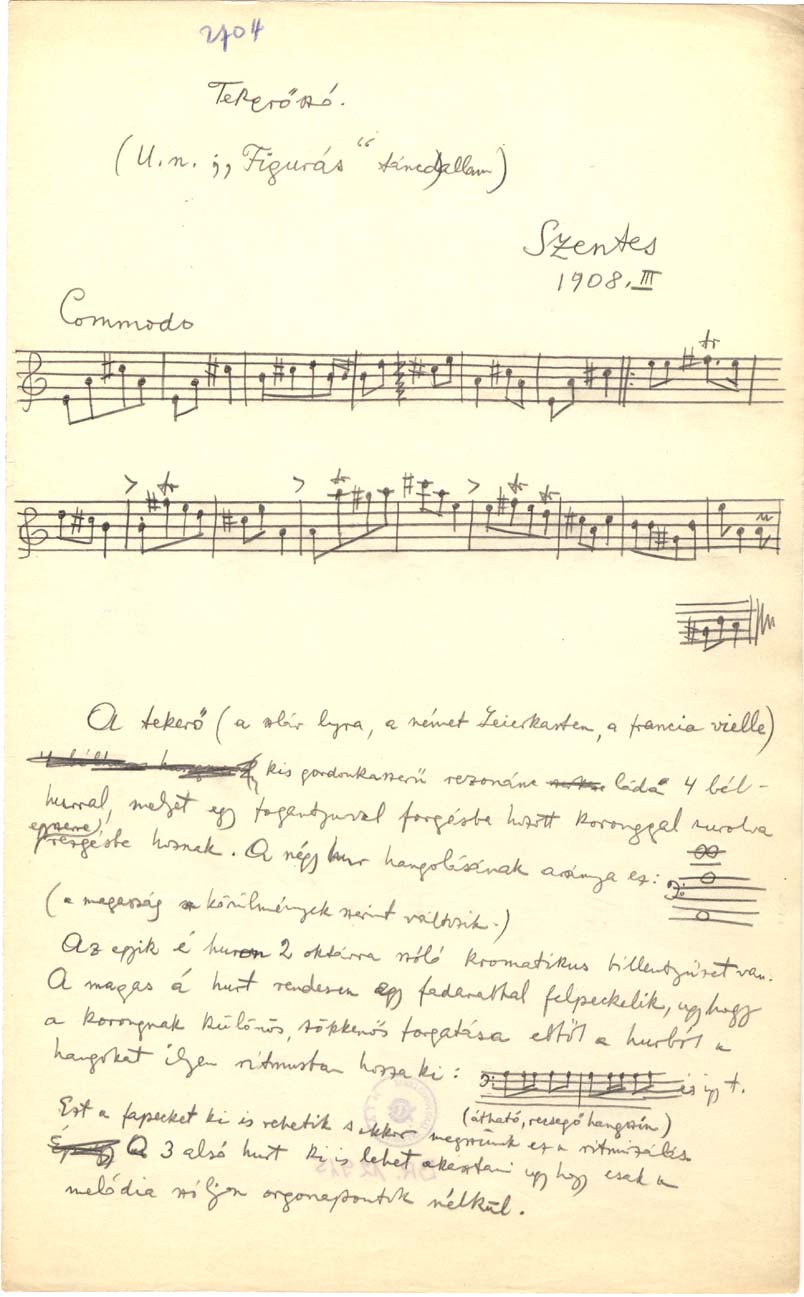

Bartók encountered instrumental folk music at the beginning of his systematic research. In 1906, he heard a hurdy-gurdy player in Szentes (Figure 4); during the summer of the same year, he probably heard some bagpipe music in the Southern Great Plain; in 1907 in Felsőireg, he recorded a vocal imitation of bagpipe-playing (Figure 5).

By 1911–1912, when he published “The Musical Instruments of the Hungarian People,” he had enumerated the instruments, described their repertoires and techniques of playing, and examined whether any specific Hungarian traits can be established on these grounds. In 1910, he organized, with ethnographer István Györffy, a bagpipe and swineherd’s horn players’ competition in Ipolyság (today: Šahy, Slovakia), which gave him an insight into the Hungarian and Slovak tradition of these instruments (Figure 6). Bartók, as he confessed in his 1931 article “Gypsy Music? Hungarian Music?”, viewed himself and other Hungarian folk music researchers as natural scientists who investigate peasant music as a natural phenomenon. Indeed, he recorded everything connected to a given issue of folk music with the accuracy of a natural scientist.

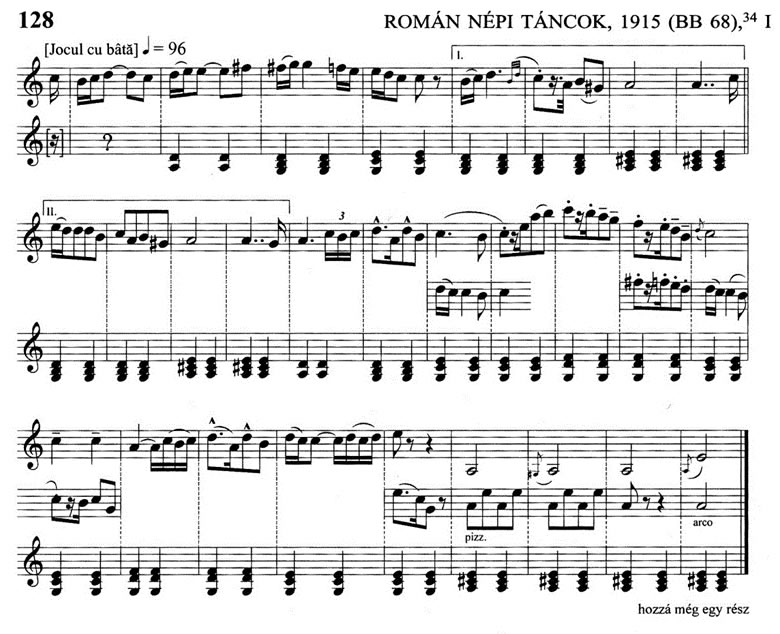

He described exactly the shape of the instruments, their tuning, the materials they were made of, and the techniques of playing them (Figure 7). He was the first to describe the three-stringed viola or kontra which later became the basic accompanying instrument of the folk music revival movement; he first heard this instrument in 1912, in the village Mezőszabad in the Transylvanian Plain (today: Voiniceni, Romania). In 1914, Bartók recorded a further occurrence of the instrument in the Görgény (Gurghiu) Valley. As is evident from the transcription of the Mezőszabad tune featured in the first movement of his Romanian Folk Dances (1915, BB 68), Bartók also recorded the harmonization on this occasion (Figure 8).

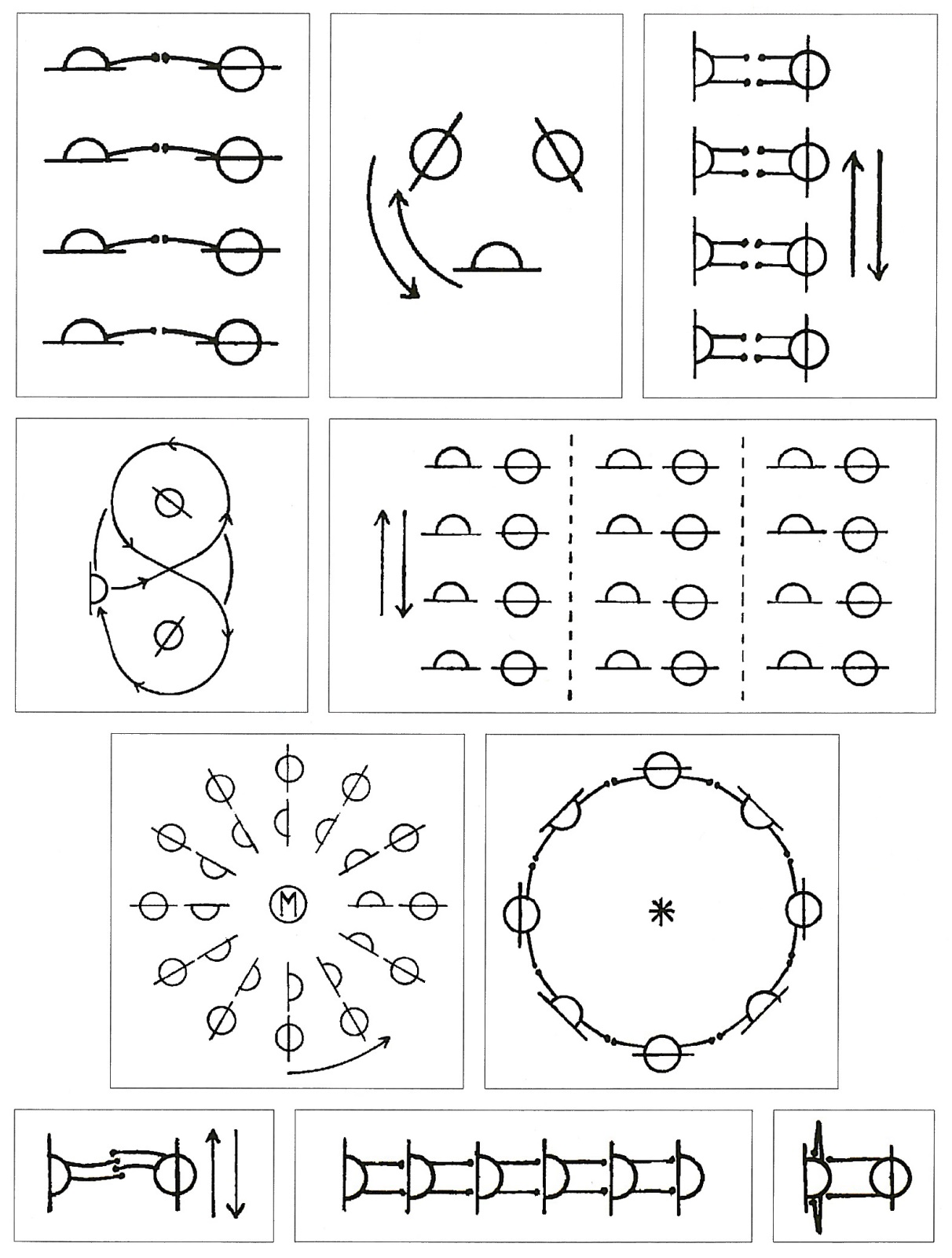

In the study published in 1936 “Why and How Do We Collect Folk Music,” still an exemplary classic of ethnomusicology, Bartók included issues of collecting instrumental folk music, also addressing the dances:

If dance music is performed, it is important to set down in exact detail the name of the dance, its steps, when and with whom it is danced, who plays the accompaniments; is the melody sung with the music during the dance and, if so, who does the singing – the dancers, the spectators, or all together?13

Bartók’s Romanian collections made 20–25 years prior to this study testify to the meticulous procedure described above. His carefully drawn schemes show that he held the dance performed to the music worthy of recording, too (Figure 9). As ethnochoreologist György Martin wrote,

Observing the dance and the music simultaneously, Bartók made one of the most significant discoveries in the research of folk dance and instrumental music as he noticed the so-called dance cycle. [...] He gave an almost complete picture of the still flourishing dance tradition of the Romanians in Transylvania, based on the entire dance stock of five smaller dialectal areas (Maramureș, the Upper Mureș Valley, Hunedoara, Bihor, and Banat).14

By the collection of folk music, Bartók meant the complex observation, recording, and transcription of events in which folklore is manifest:

Finally, I would like to call [the collectors’] attention to photography of the informant, scenes of game and dance, instruments, or other objects which play a certain role in folk music. Sound films are particularly helpful in correlating our collection with actual living conditions.16

The four main figures of the golden age of Hungarian folk music research – Béla Vikár, Béla Bartók, Zoltán Kodály, and László Lajtha – set the main trends for the exploration of Hungarian folk music tradition, which still fundamentally affect the profile and activity of the discipline. Vikár’s complex approach to the phenomena of folklore, Kodály’s attentiveness to historical sources, Bartók’s study of interethnic connections, and Lajtha’s discovery of the rich instrumental traditions – all these results determined the major topics of Hungarian ethnomusicology for a long time. If we sum up the work of these four scholars, we will obtain roughly one-fifth of the activity of Hungarian ethnomusicology, both in terms of the time-span and the quantity of the recorded material. Yet if we consider the survey of the structure, styles, and musical features of the Hungarian musical tradition, their achievement will cover no less than three quarters of our present-day knowledge, and Bartók’s contribution, still retaining its full validity, remains the most complex of all.

Pál Richter